Doing the American Hustle

“People believe what they want to believe because the guy who made this was so good that it’s real to everybody. Now who’s the master, the painter or the forger?”

“American” and “Hustle” — the words are redundant. American Hustle, the movie; American hustle, the reality.

Published on http://brightlightsfilm.com

First, the movie and its characters “doing the hustle,” like a dissonant disco party. Money, sex, greed, and ambition are at the party and the DJ is a con man spinning the discs and keeping everyone moving. Wise guys stand at the bar, the guys you fear and do not want to go near. There is a poor boy at the party, stupefied, immobile, doing the dull Federal bureaucracy hustle.

This movie has a history, shades of the carnival family life of P. T. Anderson’s Boogie Nights (1997) as well as Scorsese’sGoodfellas’ (1990) ubiquitous larceny, lust, and laughs. An even earlier film version of the hustle of sex, politics, and a con man on the loose is Hal Ashby’s Shampoo (1975). But the film actually stretches back to screwball comedies, Jennifer Lawrence like a crazed Carole Lombard in My Man Godfrey (1936) or, in a film filled with the hustle of the con, To Be or Not to Be(1942). Lawrence’s scenes as Rosalyn Rosenfeld with Christian Bale’s Irving Rosenfeld are reminiscent of a zany Judy Holiday with Broderick Crawford in George Cukor’sBorn Yesterday (1950).

It’s a whacko hustle, but now this new hustle is not sparked by a Depression-era anxiety heading toward the Dada of the Marx brothers, whose hectic mania permeates a whole society, as inDuck Soup (1933), when the brothers become the ruling government. Licentious, larcenous, anarchic, the Marx brothers turn the whole world upside down at a time when speech is cut loose from sense but money was not yet the speech that ruled.

There is a difference but also continuity, a continuity of hustling toward a madcap world in which all moorings are breaking loose and all that is solid melts into air. In the early screwball hustle films, we have the very beginnings of a post-truth world where bullshit has no boundaries. The difference between our new millennial hustle and these earlier screwball versions is that now the hustlers and the hustle can never successfully be brought to trial and the most flagrant machinations are never prosecuted. Reality and truth are no longer waiting in the wings or secure in the minds of the audience. In the post-truth world, all is perpetually in motion, intercrossing and intercommunicating with no solid external, Archimedean point in sight. You could once step out of the world ofDuck Soup in leaving the theatre and return to an order of things commonly shared; there is in a post-truth, new millennial world no such return possible.

American hustle, the practice and not the movie, the type of hustle that will lead to the 2007 Great Recession as it had led to the Great Depression some eighty years before, begins a rehearsal period with the Abscam scandal of the late ’70s, a scandal in which the con man of American Hustle tells us they never caught the big guys but just some legislators trying to bring relief to their constituents. But it’s this small con game now brought to the screen in 2013, a small potatoes con game when compared to the dark and deep intricate hustling of Wall Street in 2007, a hustle that points a finger at Big Brother and not Wall Street as the evil gamesters. Whatever untoward behavior that seems to be coming from Wall Street “whales,” deep pocket financiers claiming to be doing “God’s work,” and Ponzi scheme tricksters, all such behavior and such villainy seem to be actually initiated by a regulating, interfering governmental bureaucracy. This is, at the very least, a mind-blowing deduction, itself a bit of Rufus T. Firefly rationality. In bypassing the political minefield of confounding conclusions regarding the 2007 Great Recession, American Hustle avoids the mystifications of that hustle that still looms as an “unsolved case” with no one found guilty. However, the movie extends wider and plunges deeper into a hustle drive that infects both the American cultural psyche and the psyche of every American. This is a drive that the Puritans failed to repress and what Melville soberly glimpsed in The Confidence Man, Twain made hilarious with the Duke and the Dauphin in Huckleberry Finn, and P. T. Barnum carnivalized across America.

The victory of appearance over reality is sealed in the 20th century and extended into the infinitude of a virtualized cyberspace in the 21st century as brick and mortar, paper and ink, the physical presence of friends and enemies, work and wages, warfare and spying have all been translated to an entirely different plane of existence. Call it forgery. Irving Rosenfeld, the con artist, gives Bradley Cooper’s Richie DiMaso, the FBI agent, a lesson as both look at a painting the agent thinks is real but Irving tells him that thinking something is real doesn’t mean it’s not a forgery. The con artist’s artistry lies in this making what is not true or real appear to be so in the eyes of the mark.

DiMaso is ambitious, as is his FBI superior, Amado, but ambition itself is expanded in the new millennium beyond egoism, beyond narcissism and on to solipsism as virtual communities composed of virtual friends exist within the design priorities of individual choice. So the hustle will expand beyond the hustle of this film where the question of reality and forgery reemerges at the very beginning of our post-truth era, an era in which narratives of truth and reality can no longer be clearly seen as distinct from truth and reality. The forgery of the hyperreal that has no link to the real but stands, as Baudrillard predicted, in place of it opens the door to the world that the audience ofAmerican Hustle is in.

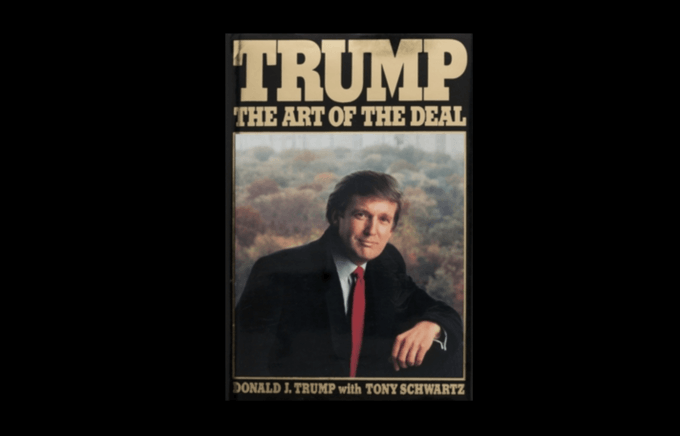

We are clued to the supremacy of appearance over reality in the first scene of the movie as Irving slowly and carefully arranges tangles of his hair into a comb-over supplemented by tufts of faux hair, all of which is glued, patted down, and sprayed into position. “What you think you are seeing,” this scene informs us right off, “may not be as real as you think.” Every movie photoshops reality, but not every movie makes this its subject. And unlike films that do, such as Blow-Up, (1966), Cinema Paradiso(1988), or Pan’s Labyrinth, (2006), American Hustle hustles us into a world not studying the dilemma but transitioning us into the instabilities and zaniness of a forged world. The film is part wide-eyed and perplexed realism (Louie C.K.’s Stoddard Thorsen), but it is not a naiveté that a hyper/hyped audience can share. Being outsidethe hustle is not anything the new millennium offers.

Every viewer in 2013 knows that Irving’s one-man game will expand to the hustle of The Great Communicator Ronald Reagan and beyond that expand in the cyber age to mind-boggling proportions. The movie chooses not to show what we know, but we already know this because we have lived it. Every viewer knows that the whole world indeed may be photoshopped online and seem true to everyone’s eyes. Replacing the real with simulacra is the marketer’s stock in trade. And the simulations of the market itself are the stockbroker’s stock in trade. The real now far exceeds Irving’s hustle, extending to insurance, real estate, cars, breakfast cereals, sleeping pills, fashion, politics, and of course, film, where spectacle is its true métier. And so whileAmerican Hustle the film seems to evade all the dark consequences of our cyberspace/post-truth world of perpetual hustle, none of this can possibly be avoided in the real world.

The film is indeed a masterful deflection of all the partisan uproar that would occur had the film pitched its tent not in Irving’s backyard but on Wall Street, like an Occupier. And that partisan uproar would not be limited to the political scene but pitch cyberspace enthusiasts against those not so enthused, and, most dramatically, Winners against Losers. In place of this entire furor, the film pulls us all into the hilarity of the con and the players while never contradicting the fact that hustle is the quintessential ingredient of American success, the very heart of Americana.

Hustle here is bullshit, as the philosopher Harry G. Frankfurt (On Bullshit, 2005) describes it. The bullshitter “is neither on the side of the true nor on the side of the false. His eye is not on the facts at all, as the eyes of the honest man and of the liar are, except insofar as they may be pertinent to his interest in getting away with what he says. He does not care whether the things he says describe reality correctly. He just picks them out, or makes them up to suit his purpose.”

Creating faux realities is easier in our new cyberspace millennial world because reality itself has been virtualized. Determining what is true and what is false has been made easier because that determination has been personalized. Empirical evidence and validation have been removed from any disinterested investigation to a personal view, indeed a personal “Like” or a personal “Whatever.” With the gatekeepers of a real or forged world dismissed from their posts, the world can go full-tilt boogie in all directions as in a three-ring circus, a hyperreal of hype and hustle.

The American economy grows on the hustle of its innovators, entrepreneurs, advertisers and marketers, celebrities and financial “players,” its hustlers, who open new marketing frontiers or lobby legislators, hustle voters who will not in any way prosper by being so hustled. After Abscam times, the American hustle will head toward a Market Rule Apocalypse that will leave the hustlers at the top and the hustled wondering what game they were in and how it was played. The focus of this movie is on the hustle dance, the rhythms, and the movements as it plays on in as many places as the film can reach. What the film seems to say is that taking a good look at this dance as the very soul of the American comédie humaine tells us more about ourselves than the events and scandals that are its symptoms. The characters are caught up in the dance; they actualize it but it’s the hustle dance itself that draws us.

Amy Adams’s Sydney Prosser wants to concoct a bullshit identity for herself and finds Christian Bale’s Irving Rosenfeld, who makes a living concocting bullshit stories that result in $5,000 checks from greedy marks. Bradley Cooper’s Richie DiMaso wants to bring the hustlers to justice by hustling them, allowing us to think that the dispensation of justice is a hustle, something perhaps O. J. Simpson’s “Dream Team” had already embedded in the American mass psyche. His FBI associates include a mid-level bureaucrat, Amado, whose ambition is pushing him to hustle up the bureaucratic ladder, and Louis C.K.’s Stoddard Thorsen, who remains temperamentally outside the hustle.

The most kinetic hustler is Irving’s wife, Rosalyn, who works a marriage hustle, in which Irving is also a player. It is as if they cannot work themselves out of their own bullshit. The marriage hustle works like this: Irving the hustler needs a reality that’s hustle-free, and for him that is being a father to his son. His son, young Irv, is like a solid that will not melt into the nothingness of bullshit. The marriage is a packaging of this true zone of the real, but it proves no respite from hustle because Rosalyn is all the movements of hustle in one body but propelled by a mind that is fractured, but not able to multi-task. She thusly represents a foreshadowing of the hyperkinetic, ADD, OCD, addictive, narcissistic reality to come.

Sex, which all the women in this film exude, in the world of hustle is a constant energy feed. You cannot seem to have a con without it as if when reality is hyped, sex is the lubricant of the hype. Sex is never off-screen, always in our face, whether we’re looking at cleavage cut to the navel, or long shapely legs stretched out for DiMaso to hold, or trim ankles getting into a car, or lips inches away from other lips. This American hustle literally takes to the disco dance floor, where heated exchanges lead to a rush to a bathroom stall for a tryst that never happens. Everything involved in the hustle is deferred until the payoff, tempting and alluring and just out of reach until then. We stay hungry, primed for the con. Sex and the hustle in American life are kept ever on the boil, never evaporating. It permeates the culture because the hustle permeates the culture. It is what an economics of “greed is good; greed works” requires. Greed thrives on the juices of sex and the hustle, the juices of the American Dream. The good con man, like the skilled salesman of all stripes, from politics to marketing to investing, is always at play, and sex is the medium of transaction, the capstone, the climax of all play.

Two notable collisions with this hustling reality barely stop the flow and dance by more than a caesura in the beat. Louie C.K.’s Stoddard Thorsen is all that his name suggests, a stolid bureaucrat without rhythm, which means he not only cannot do the hustle, he cannot hear it or see it. In his scenes with DiMaso, Thorsen is positioned squarely behind his desk, the true man behind the desk, the man defined by his job and its procedures. Procedures reveal the real. But in this film, he is really at the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party. While Thorsen remains fixed in place, DiMaso plunges deeper and deeper into the madness of the hustle, so deep that he can no longer see what is real and what is not. The hustle here now in 1978 is still analog, do-able on the off-line movie screen, but Thorsen, the bureaucrat, cannot quite keep up with it all. We sit there in the audience as he sits behind his desk, somewhat dazed and confused, seeking control by telling his “back in the day” story. Thorsen’s Michigan fishing story is an old-fashioned, before-the-hustle story, what in a few years will be called mockingly an analog story in a digital world. The hyped-up DiMaso cannot wait for the story’s closure; he has lost all patience for the world moving in an unhustled way. Each time he interrupts with his own story ending, a moral that clearly seems to be the one Thorsen was heading toward, Thorsen says no. He will not let his flow of procedural, linear, continuous reality be preempted by the erratic intrusions of DiMaso. He will not learn. He will not move. He will not dance.

There is no need to nail down truth or reality in the world of hustle, or bring the hustle, which is multiple and not one, to closure. The economic system that rules requires an endless game of hustle, an endless replacement of the real with simulacra and a continued campaign to have the profitable appear as the only real. Such a system does not wait for the need for rational connectivity, purposeful continuity, and meaningful closure. Hustle cannot wait for Louie C.K’s Stoddard Thorsen to catch up.

Not surprisingly in this P. T. Barnum world, Thorsen departs the scene of hustle victory abused and ridiculed. But Irving, the master hustler, hustles victory away from DiMaso and the FBI, the ridiculed now reinstated in a way that reality reinstates itself periodically in the hustle dance. Irving knows this; he has, here in the late ’70s, a respect for the limits of bullshit and of trespassing too far from reality. That reticence will all but vanish as cyberspace joins global Market Rule and kicks the hustle of façade, spectacle, the virtual, the hype, the bullshit into high speed.

The second notable collision between the real and a forged reality comes when Robert De Niro as Victor Tallegio, feared mob boss, sits opposite Irving, DiMaso, and the pawn of both, Jeremy Renner as Mayor Polito, and delivers the words that hard reality uses when confronted with any whiff of bullshit. Hard-faced and scary, De Niro’s Tallegio leans forward and tells the hustler that there’s no mystery when they deal with him, that what happens if anyone is trying to pull something on him will be very real, no bullshit. On the other hand, all he has from them are words and there could be nothing real behind them. When hype collides with hard reality, the result, in this case, will be deadly. Irving, the experienced hustler, knows that his hustle has to avoid possible retaliation by those he hustles. He bottom feeds on the helpless but greedy, those who become embarrassed by being hustled. Trying to hustle Tallegio or congressmen is way outside Irving’s game. DiMaso forces this game, telling Irving flat out that he’s now Irving’s boss.

We also have a brief caesura in the hustle, a fleeting image of Mayor Polito’s family lined up on the staircase, distressed as their father is taken into custody. The hustle pauses again here. This is where the con cannot go, but it does not mean that Irving has not used his Bronx background and family life as a means to bond and lure Polito into the hustle. Nothing sacred in the hustle but this yet remains something that Irving regrets, a regret that will lead him to help Polito out of the worst of his indictment, by yet another hustle of course.

It’s a crazy carnival of a hustle here in the late ’70s, one not yet accelerated by smartphones and second-by-second tweets, Facebook postings, and so much personalized high-speed online communication that has resulted in no one knowing anything in common, a blow to the notion of communication as “social.” We, the audience in 2013, know this high-speed world; we know the entire exciting tech that awaits these ’70s characters. They amuse us in their analog, “back in the day” lives. Rosalyn places metal in the new “science oven,” and the whole audience laughs more than at any other scene. And what credibility do we extend someone in 2013 who is without a cell phone? Here all characters are cell phone-less, not even a flip phone. The world is not yet online. Our amusement distances us from other, darker thoughts.

All the signs of what will be are here in American Hustle. The federal prosecutor will remain many steps behind the “wolves of Wall Street” they pursue, clueless as to how the Magister Ludi hedge fund managers ply their intricate financial cons. Compared to these wizards and their wizardry, the federal government remains a dumb show. Stolid beef-witted bureaucrats, unteachable in the sly ways of the hustle.

What camera do you think will capture the hustle of both the offline world and the online world? The world we think is not a forgery and the world cyberspace runs alongside it? We need the equivalent of an electron microscope to capture the hustle that a post-truth Market Rule world moving globally at cyber high-speed produces. The difficulty of getting this to the screen is on the level of getting the Higgs-Boson particle into view. No matter. We are no longer making an attempt at capturing the Big Picture but rather have opted for personally designed views of reality, indifferent to whether our realities are forged or not, whether we’ve been hustled, whether we’ve been conned into believing that we’re somehow outside the hustle in a separate world of our own that’s true and real.