Baseball is a spirited race of man against man, reflex against reflex. A game of inches. Every skill is measured. Every heroic, every failing is seen and cheered, or booed. And then becomes a statistic. In baseball democracy shines its clearest. The only race that matters is the race to the bag. The creed is the rulebook.

– Ernie Harwell, Baseball Almanac

Regardless of what narrative spin rules the day, we face certain inevitabilities, none of course universally acknowledged as inevitable besides death. Some inevitability seems to be a much surer bet than others. For instance, what technology, especially cybertech, offers will not one day vanish. Unless of course it loses itself in its own complexity, or, quite the opposite, its own complexity falls before some quite simple invasion, rather like the way box cutters brought down the Twin Towers. The probability is, however, that it’s pretty much a sure thing that the future, near or far, will not go offline, at least not by choice. Older generations of Smartphones, X-boxes, I-pads and so on will vanish but only to be replaced by even more fascinating technology.

Probability also leads us to believe that chemical enhancement of sports performance is such a technology that will not go away. Once “innovated” it will not succumb to any resistance but rather will shape the “new normal,” as politicians now refer to our continuing recession blues.

I think this is so, first of all, because we are very much attached to growth through technology; we prefer continuous growth economics rather than steady state/sustainable. To grow ever larger you need to expand profits and this is done by offering new products which are the creation of new technology. So our economic system, which everything else queues behind, including politics, is more liable to view sports’ performance enhancement via technology as part of inevitable growth goals.

Secondly, and connected to our competitive rather than cooperative notion of economics, we are very much attached to getting into the competitive arena and winning. Why wouldn’t the newest technological innovations apply to winning in sports as they do in our most important domain, that of economics? Entrepreneurs play a hard ball game just short of criminal arrest, most of the time but not always. The entrepreneurial idea here is to push the envelope, to go to the very edge of risk, to push a self-empowerment to the max, for the bold to leave the timid behind, in the dust.

Doping is the sports’ world’s version of insider trading: it’s illegal but the very nature of the enterprise encourages its existence.

Thirdly, we have pushed ourselves toward a need for accelerated response and an attendant impatience with “slow, dial-up speed” and certainly for the speed of the offline world. We have pushed ourselves online to virtual realities that make our offline world seem boring and slow.

Wikipedia describes a virtual game world which more and more people inhabit: “Massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG) is a genre of role-playing video games in which a very large number of players interact with one another within a virtual game world.” Ten milliion people inhabit the World of Warcraft domain for example. These cyberspace, substitute, fantasy worlds are knocking at our offline “real world” urging it to keep pace. “Real world” sports now has a competitor no one foresaw, a competitor that offers not only the enhanced performance of virtual characters but the opportunity to interact within the worlds those characters inhabit. You are no longer sitting in the bleachers watching the game; you are in the game. You don’t go out to the ballgame because it’s no longer “out there,” everything that was once “out there” is now in cyberspace. The world has collapsed into just you, virtual faces of friends, 140 character tweets, Apps for all cyber connections. What offline reality can rival this? How much doping must be done to real bodies to compete with virtual powers?

And lastly, I would say that whatever resistance we muster against the invasion of biotech into sports, it cannot withstand every form of technology’s march toward a future in which all manner of constraints and limitations are surpassed. We can stimulate the brains of infants and increase IQ; we can replace worn out or diseased organs with new ones; we aim to put a world of information behind our eyelids; we aim to mesh our nervous system’s synapse with a microchip and move from bionic being to cyborg. It seems inevitable to us that we will reach this prophesied “technological singularity.”

So what is the especial resistance sports can make to all this?

“Take me out to the ball game,

Take me out with the crowd.

Buy me some peanuts and cracker jack,

I don’t care if I never get back,

Let me root, root, root for the home team,

If they don’t win it’s a shame.

For it’s one, two, three strikes, you’re out,

At the old ball game.”

– Jack Norworth

Bryant Gumbel once said that the other sports are just sports but baseball is a love. Can I say that the heart of resistance to technology’s impact on sports is America’s love of baseball? The tradition here is built on Olympian gods, from the legendary “Bambino” like a true force of unbridled Nature to Jolting Joe DiMaggio’s disciplined mastery, to the heartfelt tragedy of Lou Gehrig “story,” the victory of talent over racism in Jackie Robinson, the perfection of Ted Williams’ swing, the all around perfection of Willie Mays hitting, fielding, running the bases, the miracle of Sandy Koufax’s fast ball. There’s a theogony here that exceeds that of classical Greece.

When you love baseball you love the game now but you love it within this great tradition in which baseball runs alongside the “birth of our nation,” baseball beats with the heart of Americana. And you do not want that sullied, tampered with, violated. You don’t want the triumphs of baseball’s legends to be overwritten by the quick fixes of biotechnology, the deck, if you will, of natural performance stacked so that winning and losing lose meaning.

Technology threatens to hollow out what has been so magnificently created. And because baseball is at the heart of the American cultural imaginary, all violations to the honesty of the game weigh heavy on the American soul. Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa and Barry Bonds tarnish the soul of sports in a way that Lance Armstrong cannot do because cycling is more closely linked to the French and the Italians and the Dutch and Europe itself than the U.S.

The resistance to the inevitability of doping in every sport fades as baseball itself disconnects from the heart of Americana. And this disconnect has occured in the new millennial cybertech generation. Red Smith accused dull minds of finding baseball dull but today it is more apt to say that all “back in the day” analogue reality is dull in the view of those like Jane McGonigal of the Institute for the Future who in her TED talk called for at least tweny-one billion hours a week of game play in order for us to solve the world’s problems and insure the survival of the planet. The virtual game here is one in which the players are not on an offline field but on a virtual field and winning is something they can achieve by gaming in cyberspace. The “epic win” is the reward for deft play and smart choices. It is an individual not a team win; it is personal and not social; private and not public. All this meshes nicely with a broader American cultural mind-set.

Baseball cannot move as fast, cannot jump cut, sidebar and enable the interaction that cybertech can. It cannot make everyone in the bleachers a Derek Jeter. The winning cannot be as personal; it can never be interactive as long as it is offline. If Cybertech has both over-stimulated and abridged attention span at the present three billion hours a week of online gaming, you can imagine that at a recommended twenty-one billion hours a week, a virtualized online reality will be jacked up to levels of interaction and affiliation against which offline reality, for all the vagaries Mother Nature as well as human nature throw at us, cannot compete.

And yet it tries because our offline sports are still multi-billion dollar businesses. Therefore we now face, and perhaps only for a brief transitional period, the urgency of enhancing all aspects of offline sports to keep pace with the acceleration of fragmented stimulation. Doping is both a response to this state of affairs and part of the technological advance that has created it.

The superheroes of pop culture, including all the heroes of online gaming, of TV and film, are struggling to inhabit the sports fields, accomplishing the super-human feats that performance enhancing doping allows. A new notion of what skill and strength are, of what endurance and agility are, of what a championship level of toughness is becomes inevitable as every sport succumbs to the ubiquitous presence of doping, as every sport revs itself up to meet the accelerated awareness that our cybertech new world has created.

A good part of our baseball mythos in America is to believe that its legendary heroes of the past would be too proud of their own God given natural gifts, their own natural and trained prowess, to accept an “enhancement” from the tech lab, an “enhancement” available to all and therefore ultimately destructive of one’s own natural and trained prowess. But we live now within a technological mythos that grants to technology the power and beneficence of the Greek gods. Only a foolish, archaic luddite would deny technology its superiority over the unenhanced functioning of brain and muscle. What is “natural” has come to be seen as only that which an offline world has, because of its analogue roots, defined as “natural.” Digital reality is in the early stages of extending the notion of “natural” to levels that remain inconceivable to us now. We are more focused on that as yet inconceivable future than we are on what anything might have been achieved in the past. Babe Ruth’s record is not diminished if we believe that a technologically enhanced world, the world of baseball as well as all sports, are themselves enhanced. The playing field, if you will, is different, alternative, and preferred.

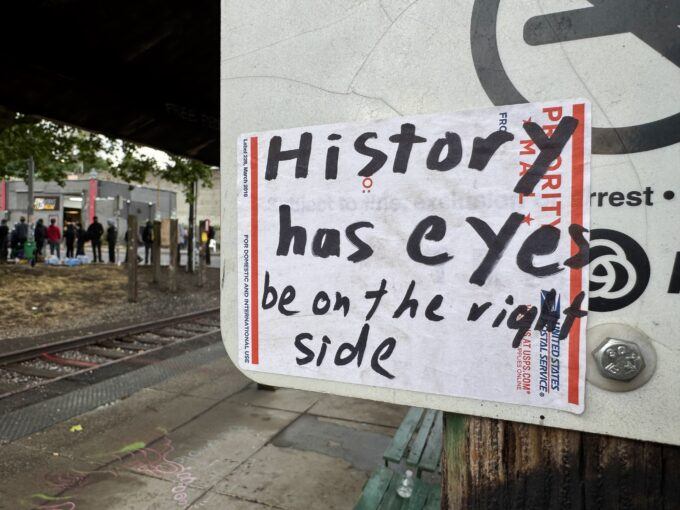

Right now only historical memory resists this.

What we could do with our chemically unenhanced bodies, what kind of toughness, strength, and endurance we could summon without technological prosthesis, what we could do when Nature rocked us hard throughout our history is not an insignificant record, though our online realities accelerate the obsolescence and extinction of all historical recollection.

I think of sports as a grueling challenge, in some ways more than others, as making demands of body and mind, of deftness of hand and foot, as summoning a force of intent to go a step further, to give more when the body says it has no more to give. I think of it as a physical and mental toughness directly opposed to any biotech trespass, as opposed to any artificially “enhancing”intrusion. To own your performance is to own your body, to reject its purchase by the newest, under the radar doping.

This now appears to be a nostalgic, romanticized view, one that faces not only the relentless progression of biotech and cybertech but the bedrock creed of zero-sum, winner take all competitiveness that drives our prevailing cultural narrative.

Postscript: If you want to know what physical and mental toughness and courage is you need to watch Captain Irving Johnson’s film of a wrong way voyage around the Cape in the tall ship The Peking, filmed by Johnson in the toughest storm in the North Sea on Friday the 13th, 1929 and narrated by Johnson some fifty years later. You need to listen to Juan Jose Padilla, the matador called the Cyclone of Jerez, a one-eyed torero who says proudly that his profession is the most dignified in the world because of its truth, its reality. A “new and enlightened” Spain may now totally outlaw the bullfight, refusing to accept “the truth and reality” of what the anti-taurinos see as barbaric. What I see here is rivaling notions of truth and reality: on one hand, these are to be found in a clash whose power emerges from its direct encounter with mortality; on the other hand, these are to be found in the notion that what an enlightened civilization does is distance itself from this fiesta brava, this “wild feast.”

May 2013

From guest contributor Joseph Natoli

For my dear friend Einar Nordgaard