West Virginia

Published on http://truth-out.org

“McDowell County, the poorest in West Virginia, has been emblematic of entrenched American poverty for more than a half century. John F. Kennedy campaigned here in 1960 and was so appalled that he promised to send help if elected president. His first executive order created the modern food stamp program, whose first recipients were McDowell Country residents. When President Lyndon B. Johnson declared ‘unconditional war on poverty’ in 1964, it was the squalor of Appalachia he had in mind.”

– Trip Gariel, “50 Years Later, Hardship Hits Back,” The New York Times, April 21, 2014

“You can’t just come in the neighborhood and start bogarting and say, like you’re motherfuckin’ Columbus and kill off the Native Americans. Or what they do in Brazil, what they did to the indigenous people. You have to come with respect. There’s a code. There’s people . . . So, why did it take this great influx of white people to get the schools better? Why’s there more police protection in Bed Stuy and Harlem now? Why’s the garbage getting picked up more regularly? We been here!”

– Spike Lee, film director

“Are you sure you heard a ping from a black box, and if so, where did it come from?”

In the ’70s, when I lived in the original, 200-year-old Oxley Hollow homestead outside Athens, West Virginia, in a county neighboring McDowell, Mercer County, I noticed the ubiquitous presence of JFK’s face on cabin walls, like the ubiquitous face of Jesus, often in velveteen brightness. I had New York plates on my 1972 VW camper and a noisy muffler, and I told folks I was from Brooklyn, describing a difference between that borough and the others that was lengthy, ferocious and bewildering to all. I farmed land that had not been farmed in many years, answered the call to help folks out, and though I announced myself a “Catlick” (Catholic), I was told that “we ain’t gonna fall out over that.” After all, JFK had been a “Catlick.” If not for him, Troy told me, with a twinkle in his eye, “some fellars might have burnt a cross on your lawn,” not that any area where my wild chickens terrorized my dogs could have passed muster as “lawn” among the Michigan neighbors I would have some quarter of a century later.

I owe my survival in Oxley Holl’er to my neighbors.

So, a Borough Park, Brooklyn boy with a “Talley” last name became “Joe Nat Lee” who lived “down there in Oxley Holl’er.” We put a bell around our 2-year-old daughter’s neck so we could hear where she was, kept our two city dogs on a runner so they wouldn’t spring one of the fox traps that were all over (fox pelts worth $50, a huge sum to all) and in a year or so rushed out of that holler so a second baby could be born minutes after we arrived at Princeton hospital. She was born, today’s The New York Times tells me, amid the unconquerable poverty of southern Appalachia.

I know too that she was born surrounded by people who looked out for each other, who joined with me in the coldest winter to fell trees and cut wood when mine had run out. I had scant dollars to pay Coy and Tom for wiring my house, but for them, even the little I had was too much. “We’ve had enough,” Coy told me, shaking his head, refusing the 20 dollars I held out to him. In turn, I helped put up a barn, plant ‘taters, burn winter grass, feed horses and cattle, and shovel a path to a cabin for an old woman who left the hospital in mid-winter and wanted to die back “down there in the holl’er” where she was born. I owe my survival in Oxley Holl’er to my neighbors, to Mr. Parker, the retired high school principle who ran a hardware store, sold his goods at Depression-era prices and gave me without cost wisdom of Appalachia beyond wiki and Google. I worked alongside the Rev. Callier, who sharecropped and picked cotton as a boy in Georgia and who showed me how to farm that Appalachian mountain soil.

As the Vietnam war dragged on toward a maddening, always-deferred ending, I sought escape in Appalachia, not searching for the ping of poverty but only to be away from the ping of a mindless war, as deeply as I could go into a small world of spellbinding difference.

The American cultural imaginary has descended into an imaginary painfully similar to medieval feudalism.

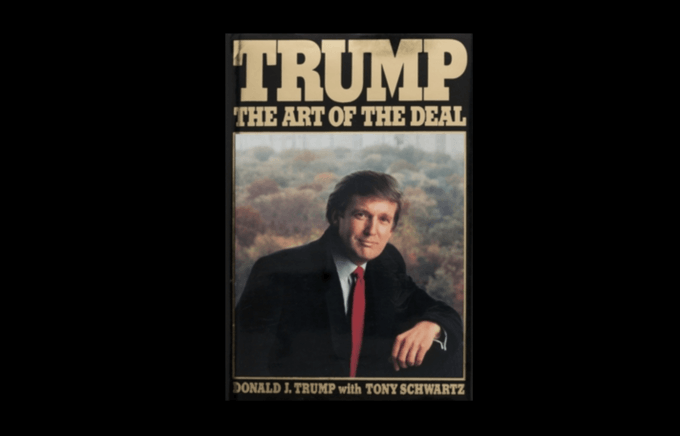

Time has provided a perspective so that one sees both a personal and cultural imaginary at work, a kind of buffering screen through which what is there and what is really going on is filtered, like a lens over your eyes. The imaginary trumps whatever any second order of observing reveals as fact and figures. That imaginary does not ignore facts from the outside, but they nonetheless have no real impact, as if they were conceivable but out of place in that imagined space of self and world in which you live. Although we believe that sanity and reason avow that we live not within a mediating imaginary zone but within reality itself, we nonetheless live within narrations of the real, in what the phenomenologists call lebenswelt, or life-worlds, our being in the world of time, objects, other people and self-image. The most powerful stories of what is what, of what anything is to mean and how it is to be valued, shape our personal thoughts, beliefs and feelings.

Time also provides a perspective on how our cultural imaginaries have changed. After a long period of economic and social mobility from WWII to Ronald Reagan, a period in which working class heroes joined and fought for working class unions, in which a middle class did not conceive of an underclass as a danger to themselves or imagine it as a “Moocher” class, in which the poor weren’t poor because they lacked the will not be poor, the American cultural imaginary has descended into an imaginary painfully similar to medieval feudalism. Within that debased imaginary, we do not search for the ping of poverty because only the poor can help themselves. In our Millennial imaginary, we are what we choose and will ourselves to be.

The mutual interdependence and sustaining interrelationships that I experienced in Oxley Holl’er are now not comprehensible because they lie outside an imaginary that extends from narcissism to solipsism, that cannot respond to any societal ping because any idea of society, of others, has vanished, or remains the archaic platform of liberals, or, worse yet, socialists. LBJ’s “War on Poverty,” 50 years later is like an alien undertaking we perceive as quixotic, but also as pointless because the issue itself does not require a collective, national action, such as real war, but only a personal response. If you do not want to be poor, start a business. Or, say “NO!” to your poverty. Poverty is not a black box we are searching for because now we know that it is just something you personally own and can disown at will.

Before I left Oxley Holl’er, I saw a glimmer of what was to come in southern Appalachia when the first franchise fast food emporium opened. A “Long John Silver’s – Think Fish” drew lines of curious people far and wide. To me, that journey from notched cabin to franchise fast food was like an omen of what was to come, of what I had seen as desires were spun as needs and what was real was exchanged for simulacra. In the years I worked at the Bluefield State College library, in the beginning on night duty till closing, I got close yet again to battles for justice and protests for basic rights that no one ever escapes. I met coal miners seeking help for black lung claims against the mine owners. One night, two young women who had been turned away from jobs at a coal mine sought my help in tracking down applicable West Virginia law to make a case of discrimination. They had come far for these jobs that paid $55 a day, and they were fighting mad that men were hired and they were not. These young women knew about Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, the fiery opponent of mine owners and politicians in their pockets, and they knew about the way the heroes of the Matewan Massacre, Sid Hatfield and Ed Chambers, were murdered by Baldwin-Felts detectives. They knew that the appellation “red neck” applied to those brave miners who made a stand at Blair Mountain against the Coal Commission. In short, they knew the historical line of rebellion from which their own protest emerged. I had escaped nothing.

I left Oxley Holler before the practice of removing mountain tops in search of coal began. The MCHM (crude 4-methylcyclohexanemethanol) leak of chemicals into the Elk River in January 2014 is the third major chemical accident in a state where both the legislature and regulatory agencies proceed, or not, at the behest of the coal and chemical industries, which dominate the state’s economy. Chemical toxins are a byproduct of an industry whose union, as unions elsewhere, no longer has power to protect or restrain mining operations. I never witnessed “family disintegration,” but rather close bonds between family and neighbors. Family breakup in southern West Virginia did not become a calamity until the 1990s, after southern West Virginia lost its major mines in the downturn of the American steel industry. Prescription drug abuse, which now devastates the region, stands like poverty itself as what closely bound families and church communities, what a perpetual stream of revival tent gatherings, what a mutual sharing of each other’s burdens had previously fought to a standstill. A communal life-world which so much of the United States had neither pursued nor cast aside with a cold credo, of “I’ve got mine, you get yours,” was alive when I lived in Oxley Holl’er.

When I read of Brooklyn’s “ascension,” I think only that my Brooklyn working-class neighborhood had no need to rise beyond what it was, was never either high nor low, gentrified or not.

Poverty and hard times did not eventually bring a resilient way of life, an existential strength that stretched beyond the individual and into the community, to the sorry state today reported in The New York Times. An overpowering American cultural imaginary, grounded in exactly the opposite of mutual aid, sharing and communal concern, displaced and conquered these virtues, tied them to values that made you a “Winner” only if someone else was made a “Loser.” What I had experienced in Oxley Holl’er was already scheduled for extinction by the rapid ascendancy of a market-driven politics. I guess there was something socialist in a society of closely woven interdependence. And as to this day, there is no gentrifying interest in Oxley Holl’er, I did not stay to see the tragic “translation.”

At the same time, I am reading The New York Times front page story “50 Years Later, Hardship Hits Back,” describing poverty in southern Appalachia, citing towns that were part of the world I had been in, I read in New York magazine “Brooklyn’s Ascension is Official.” Brooklyn is a gentrifying frontier for young cybertech/Wall Street professionals working in Manhattan. Their medium is money; their gift, their refined tastes in everything from dining to nannies. For them, Brooklyn is a formless possibility awaiting a high-end transformation. Wealth is the sole substance of gentrification; if you do not have it, you do not exist. The middle class is therefore like the underclass, i.e., simply not wealthy and therefore excluded from the habits and lifestyle of gentrification. A gentrified manner of living supported by money alone has license to overrun what it witnesses as “poor,” a new norm of being poor that claims the truly poor as well as a struggling working and middle class. Gentrification hears the ping of poverty everywhere it has not yet colonized; rescue is not the intent but ingestion, like the hungry to the sound of a dinner bell.

I know neither an inchoate Brooklyn nor a hopeless West Virginia. I lived then neither in the Appalachian poverty that we revisit as we revisit our “War on Poverty,” nor in any vision of what my Ft. Hamilton neighborhood in Brooklyn would become. I see both places now set up in our millennial view as polar opposites, framed, like the portraits of JFK and Jesus in a dovetailed notched cabin, within a way of being and seeing that was blind to how anything actually was or seen to be from an outside perspective. Each place was enveloped within a narration that disclosed a way of life that had a history, had heroes and villains, had hope, hard times and happiness, noble acts, silly and sorry dreams, awesome revelations and dark suns. I knew no one in Oxley Holl’er who saw themselves as those who today read The New York Times article see them. I see only proud, tempered faces; I see bedrock faith and communal caregiving, hear words weathered through like old boots, wise and never yielding, no matter the hardship. And when I read of Brooklyn’s “ascension,” I think only that my Brooklyn working-class neighborhood had no need to rise beyond what it was, was never either high nor low, gentrified or not. We could not know or care that “the guy with the most toys in the end, wins” and that what we already had, would not do, that if you were not a Winner you were a Loser. We did not know “The Secret” of a self chosen “will to power.” The “gentrifying” way of measuring what we were was unknown.

Sometime in the late ’90s, I returned to Brooklyn and overheard a conversation in which a friend had suffered a collapse and “no longer wanted to be rich.” He needed to go to a Revival meeting, I suppose, but not one to confess having fallen away from Jesus, but rather having fallen away from wanting to be rich. A much older Brooklyn maxim had been very different, closer to what Bernstein tells us in Citizen Kane: “It’s not hard to make a lot of money, if all you want to do is make a lot of money.” Jobs that paid a living wage, unions that fought for worker rights, a tuition-free city university, dependable pensions, the absence of credit cards as well as an “I shop, therefore I am” ethos and a respect for labor created a world that had no need to send out a ping of poverty. There was no existential distress.

More than all this was the fact that economic status and political party were not as significant in our lives as the everyday customs, habits and affiliations that bound us and were kept alive by daily face-to-face encounters. In my walk each day to the local stores with my mother, she heard stories, told stories, became informed, laughed, cried, questioned, and like a bee from flower to flower, tended the spirit of our neighborhood. We thrived on the persistent interaction with each other, exercised our understanding of others’ lives, extended imagination and empathy, saw in the plight of others, ourselves. The nexus was not cash, but the intangible connections that you could not just bid for, move in and own. The communal network was grounded. The vitriol and deception of anonymity could not thrive.

I witnessed the “descendancy” of my neighborhood in Brooklyn commensurate with the denigration of the working class as an economy turned from productivity to the Dark Arts of Wall Street financing, from unions back to the noblesse oblige of owners who felt no obligation to improve salaries or working conditions. I witnessed a collapse of a sense of security and well-being that was content with what it had and did not yearn for the ease and plenitude that seems now to signify what the American Dream has meant all along. Those who did not yearn for more, faster and easier could not easily imagine what more was needed, whether the speed of anything meant anything, and whether it was wise to make “easy” a cherished value.

We have given up communal concerns and investments in each other.

What we see now in this first quarter of the new millennium is a kind of liminal life for the middle class, a confused sense of being as neighborhoods virtualize, neighbors become “friends” on social networks in a radically different form of sociability, one that narrows society to your own “likes.” The American middle class is transitioning to something I do not expect to see. It is being translated, as Nick Bottom says in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, into some new yet unrecognizable form. But perhaps what that may be is already observable in the bottom 40 percent of the population who are absent at the poll booths, who collect no shareholder dividends, who are invisible in “quality of life” assessments. They no longer send out any ping. And no one is searching. Existential distress follows economic distress “if all you want to do is make a lot of money.” Life worlds, personal and social, are not grown by the economy alone, or, as I discovered in Oxley Holl’er, dependent upon it.

I am not alone in failing to find American locales where the images of Winners and Losers, Gentrified and Moochers have not overwhelmed values and beliefs indifferent to such. The middle class in America is living on the fumes of former security and well-being, faint memories of not yearning for what we are, each second now, stimulated to yearn for. We have given up communal concerns and investments in each other. We have given up a variety of ways of being in the world in a variety of different places. We have given up a plentitude of close relationships with nature and each other and have bought a gated, privatized isolation that defends us from each other, an anonymous virulence and cold-hearted mockery and disdain for those “below” us. What has been erased is the humanity of the human life world, a sad fate we subliminally recognize. Such recognition explains our drive toward a robotic technology that will extract the human. We are not in love with what we have become.

It’s a terrible cultural imaginary we now live within, and both my West Virginia and my Brooklyn have been casualties, not simply because we are very far from taking any societal action to relieve poverty anywhere or because Brooklyn is now becoming a District 9 sort of place where the ungentrified are very rapidly been uprooted and enclosed, like public schools now colonized by charter schools financed by Hedge Fund managers. What is most objectionable is the destruction of lifestyles that had greater merit, greater humanity, greater equality, neighborliness, social identity than the Winner/Loser/Gentrified/Ungentrified cultural imaginary that now filters all our perceptions. Call it the loss of existential habitat, the usurpation of a communal life-world built on values and meanings by a culture dominated by market values. What has been dissolved now leaves only poverty to be seen.

Gentrification is the everyday praxis of plutarchy.

McDowell County, The New York Times reports, “was always poor.” Economics creating asymmetrical power and a politics obliging that asymmetrical power erodes the human life-world the way earthmovers, dragline excavators and bucket wheel excavators wear down a mountain top. What is exposed clearly then is the various forms of debased and insulted life that poverty creates.

The close knit community of concern I found in Oxley Holl’er slips away as poverty replaces that wood burning stove we all gathered around, the inescapable and utterly controlling element in lives that previously were not weighed down by thoughts of their own poverty. Now we all ask: What could be more central and essential than having money or not having it? Now when the places I knew that I could point to and say, “There, there they seem not to care about who has money and who doesn’t” are no longer there; I have only memories. Gentrifying my Brooklyn neighborhood will not bring it back because none of the values and interests of gentrification were ours. Gentrification is the everyday praxis of plutarchy. Waging another “war on poverty” in Appalachia would only be yet again a war to turn Losers into Winners, and that is a battle no one I knew in Oxley Holl’er was fighting, or even knew about. A war to turn the poor into Winners apparently begins with a reduction of funding for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which in the Tea Party view encourages dependence on government rather than on the casino roulette spin of Wall Street speculation.

Clearly, not all pings are equal. When you believe that someone else’s poverty is someone else’s problem, only a scam ping sounds. We are heading in the opposite direction from recognizing poverty as social. Our personal choice is to dream of wealth, not poverty. Poverty wears no clothes you would ever want to wear, has no line of credit, offers no relief in shopping, cannot afford to go online or buy that new hybrid to save the environment. The new gentrified class hears the ping of not being able to get their newborn into any of the 40K or so pre-K private schools in Manhattan. If Little Italy in San Diego reverts from its gentrified lifestyle back to the working class neighborhood of yore, or if any now-gentrified Brooklyn neighborhood made the same return, that would sound as an awesome ping, a real threat, and a collapse of future well-being. A ping sounds in our new high-priced enclaves when you cannot find your favorite artisanal cheese or the staff at Suzuki or Montessori schools for 4-year olds is not appreciative of your child’s genius or when a homeless man accidentally wanders toward a baby-stroller pushed by a nanny ready to dial 9-1-1.

Imagine that the smartphone you hold in your hand and mourn the loss of so deeply that you insure it, that without it, life would end, is what poverty denies you. Impoverished, you cannot add the newest App or just use your GPS or upgrade to the Galaxy 5 or use Foursquare to see where your friends are. You cannot text or tweet. Your world grows dark. Poverty can’t bid for that $2 million condo in Park Slope, Brooklyn, fly to Rio for the weekend, or enjoy dining in the new haute Brooklyn style, and your child won’t get that real American pre-K head start at Riverdale Country or Columbian Grammar for $40,000 a year.

The idea of an egalitarian democracy shapes a cultural imaginary of societal concern; the establishment of a plutarchy shapes the opposite. Our brand of capitalism, a stochastic, Wild West play of increasingly opaque and questionable financial wheeling and dealing conducted by the super salaried has led to plutarchy, one in which, as Thomas Piketty points out in Capital in the Twenty-First Century, leads to a second Gilded Age of inherited wealth and family dynasties. The impoverished are no more than Losers who can resurrect themselves as long as no one and no society intervene. The working class is slated for extinction, and, on the way, it must suffer a loss of reputation, a loss of privileged place in the American cultural imaginary. First, the unions are demonized and then the workers themselves, workers who refuse to become high-tech skilled, refused to be retrained, re-educated, re-programmed, refuse to be the flexible pawns a globalized techno-capitalism demands. The middle class is in shards, their neighborhoods open season to invading hordes of gentrifiers, or left to rot, like the once-vibrant neighborhoods of Detroit. Rich, fertile and sustaining framings of everyday life, ways of imagining yourself and your neighbors, have been demolished like old buildings standing in the way of new multi-purpose real estate developments – high-priced condos, high-end shopping and new haute dining.

A scourging and burning, raping and pillaging of our former communal imaginaries, of what I lived within in both Borough Park and Oxl’ey Hollow, stands as the most criminal, stands to be the most indictable. Appalachian life-worlds and “un-gentrified” Brooklyn neighborhoods that signified much more than being impoverished, which did not bend to a measurement of Have and Have Not, are black boxes to an imaginary that has no imagination, that hears no pings from a ravaged nature or a democratic egalitarianism now mocked.

And the ping of poverty? Steeped now as we are in a plutarchic imaginary, poverty is a ping that if you hear, you do not want to pursue. It is a ping coming from a black box you do not want to open because it not only contains what we have lost, but what we have destroyed. If we search for it, we find a poverty that is the price the many pay for the triumph of a few in this plutarchic order we are busy gentrifying.