Empty Wall

Published on http://www.truth-out.org/

“We see the anger, but we don’t see the mourning. I think these people are in mourning for a lost way of life, for a lost identity.”—Arlie Russell Hochschild

It is always difficult, philosophically speaking, to establish what we can know, of ourselves, others and the world around us. Diagnosis, like interpretation, is difficult. If both miss the mark, remedy and understanding remain ineffective.

Our search to understand in the realm of politics already assumes the existence of a common understanding for which we are in search. Dictatorial regimes do not have to make this effort because there is no clashing partisanship, no need to package an understanding that will confront a challenging packaged understanding.

Opposing political parties in democratic republics need to build coalitions of common beliefs and views, and this cannot be done by ignoring the meanings and values already in sway in the society. Unlike a scientist, a politician seeking office cannot go off on a value-free, ideology-neutral examination of a problem. They are bound by and within grassroots perspectives, doing politics within existing societal dispositions where some stuff is popular, some barely tolerated, some ignored, some inconceivable.

What a culture ignores cannot become a party platform plank. Global warming, for instance, is an example, mostly ignored in this election. And trying to make what is inconceivable or unpalatable in a culture at a particular time conceivable or palatable is political suicide. For example, the word “socialism.” Partisan tacticians ferret out what an opponent is running from and makes it public, loudly and repetitively.

Hillary Clinton’s email is an example, as well as her $225,000 talk at Goldman Sachs. Donald Trump’s tax returns as well as his “birther” link. Clinton decided to embrace a number of Bernie Sanders’ well-supported issues, the wealth divide and free college tuition, two of the most notable. Trump embraces what spews from the worst angels of our nature for a slighted amended reason Willie Sutton said he robbed banks, “It’s where the American mass psyche is.”

There are a lot of votes, perhaps enough to win the presidency, to be gotten from those who feel cheated by a rigged system, whose disaffection has either been triggered by nightmares of liberal attempts to take away guns or abort babies days before birth, or by president Obama and “Obamacare,” or by a corrupt “liberal media,” or by trade deals and undocumented immigration that are pushing the wage-earner to extinction. For many, these are nightmares embedded in the American mass psyche.

Trump campaigns under the Republican banner, though he’s walked over their ideology without apology, because anger and revolt targets Obama and liberals more openly and dramatically than it does Wall Street’s or Ayn Rand’s Dark Arts, whose complicity in their immiseration remains opaque to them.

Also opaque and dark in the sense of evil in the view of Trump’s followers is Bernie Sanders’ Democratic Socialist critique of what has gone wrong with the US. Trump has bypassed cogent critique and the belabored “connect the dots delivery” of Sanders, and instead has adopted only a set number of rallying cries of combativeness, the only way to reach an audience already distrustful and dismissive, a profile that Trump himself mirrors. An empathy bond so created overwhelms explanatory discourse, either Sanders’ one on the left or Paul Ryan’s on the right.

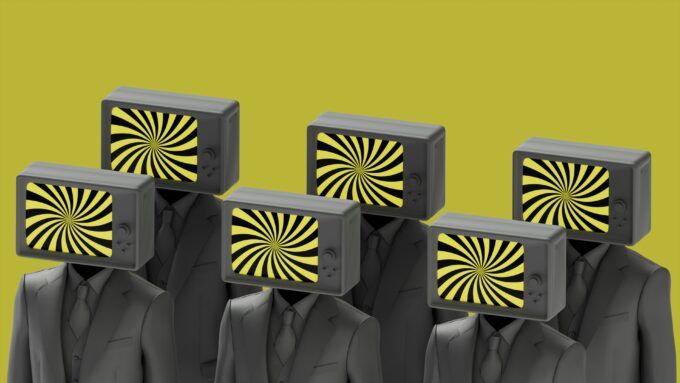

There are a great many complexities, ambiguities, contradictions and paradoxes that all efforts to reach voters on tacit, pre-reflective level must leave out. All matters must be polarized and neatly categorized as right or wrong, true or false. Those who can reduce matters to a memorable pithiness win the debate and recruit followers. However, in trying to create an affective bond of empathy, there is a blindness that a real politics, as conceived by Aristotle for instance, must overcome.

Ideally, we should all be working toward replacing ready to hand stereotypes with more penetrating interpretation and deeper understanding. While we wait for that, we need to recognize that our arguing and our thinking, our truths and our realities are unreliable and not helpful in responding to the various plights into which such reductions have gotten us. In short, we need to re-direct our suspicions and indictments from where Trump has directed them to ourselves, not that we are the guilty we have been looking. However, our own opinions and gut responses have locked us into a narrow frame of seeing that preempts any recuperation.

Social media is a welcome refuge, a safe space, where friends can amuse each other with cute videos, witticisms that do not require a trigger alert. Friends who violate this treaty of cyberspace are de-friended. Those who stray from comforting Hallmark hall vapidity, emptiness and a passive aggressiveness called subtweeting, an “underhanded insult slinging,” can make a sort of primitive return to everyday life and society in the flesh. In other words, abandoning cyberspace is an exile into irrelevance.

Social media is not, however, an innocuous space where coteries of friends can interrelate. It is also erecting fortified enclaves, assault battalions and mobilizing forces committed to mounting offensives against whatever and whoever is angering them. Certainly, this has all happened before in the analog world, leading to uprisings and revolutions, new parties, new heroes, new villains. But think of cyberspace as facilitating the expressions of everyone as well as creating online solidarities of all kinds.

In essence, everyone can find kindred “true believers” in this alternative reality And when you live more on your smartphone than in the world itself, this sort of camaraderie is made real, not “Real” but a simulated real in Baudrillard’s sense, but more real than what we have termed in Western tradition, reality.

If we are to cross the empathy divide, our smartphone apps, our tweets, our Facebook postings, our podcasts on YouTube must be the medium of transport. This is not a promising state of affairs, but it is not one we can presume will change. The ubiquity and power of cyberspace interrelationships which exclude differences that are personally offensive or unsettling does not help us cross the empathy divide, but rather entrenches us within confirming enclaves where illusions and delusions are as likely to be confirmed as truth and reality. There is a cultural pathology that manifests itself in the scenario of the cheated turning to a cheater for help but there is also a scenario in which the narcissist turns to a self-designed cyber-reality to gratify a personal and not social agency. Trump, a masquerading confidence man, seized on the former but the latter has been on the brew in the American mass psyche for a long time.

Our lack of empathy with those who we perceive as outside our configurations of truth and reality originates with a failure of self-reflexivity, a failure to jump back and scrutinize our own attachments, our own priorities, likes and dislikes. The very nature of our American clime dissuades us from such self-interrogation because we are self-empowering, autonomous, not to be refuted, arbiters of all matters. The seeds of the illusions of individual freedom and power lie deep in the American historical memory.

There is a politics of personality and celebrity alongside a politics of personal reality determination at work here, not unusual in a culture in which the simulacra and spectacle of the hyperreal is far more enticing than economic fears and frustrations and the anxieties they cause. What we observe is a very personal imaginative journey, one in which you see yourself in someone else. In movies, it is usually the hero. There is a spectacle that attracts you, that is bigger than your own life but at the same time attached to your life. Trump, the celebrity, famous for being famous, has played to the supremacy of personal opinions, paying no attention to illusions and delusions, but publicizing them without fear of disproof.

For all their immersion and affinity to the hyperreal, Trump’s followers are hard boiled, having lost faith over time in the authorizing and validating agents of truth — from government, politicians, media and scientists — and have fallen back on their own opinions as to what are the facts and what are lies and/or bullshit. Rather than become informed and sort through a clash of ideas, which have already been preempted by their distrust, they seek what they think in the personality of someone with whom they can identify.

Common opinion holds that there is no authority to shut Trump down, and that attitude preceded Trump in the American mass psyche. His opinions were theirs and like theirs could not be refuted. When he responded with “Lies!” or referenced non-existent polls and supporters, or cobbled together incoherent interpretations and explanations, or made vicious attacks on people right and left, it was all readily digestible. It was all good because none of it offended or trespassed against a cultural meme that denied the existence of truth and reality anywhere but where you personally said it was. Or where Trump said it was because there was now no difference between your personal life-world and his.

Utterly irrational and fantastical; but history has seen such strange phenomenal alliances before, a demagogue’s ability to mind meld with his followers and exude an empathy that rings true. Trump has crossed an empathy wall that has increasingly separated politics and politicians from the demos, the common people in a democracy.

This is not an insignificant accomplishment in a society that has a plutocratic level wealth divide producing a gentrified class with a diminished view of “the common people,” who are themselves sinking into a life outside any known view of society, shorter than the span of the wealthy, poorer than their own parents, and nasty and brutish in a cyberworld that gives only illusionary relief to the solitary. Trump has worked his way into the heart of those who feel cheated and has confirmed their fears and suspicions as to who the cheaters are.

What shapes a feeling of being cheated by all resident institutions has almost all to do with the devolution of a middle class democracy and the rise of plutocracy. A disastrous wealth divide didn’t just happen; it axiomatically evolved from a bent capitalism. And now those on the dividend receiving side find the lives of those living on the wage-earning side incomprehensible.

Thomas Frank, in What’s the Matter with Kansas asks: “How could so many people get it so wrong?” How could those, in his view, who have been discounted by the right, keep turning to the right for redress? How do you vilify the federal government when it is clearly the only force able contend with an unbridled globalized, financialized capitalism? What else but the solidarity that the federal government represents could stand up to an economics bending politics to its will? And so on.

The answers here are obviously that the discounted and disaffected do not believe they have got it wrong. They believe they have got it right and they will scream in your face or on Twitter to convince you. On the everyday, life-world level what the wealth divide has done is fashion an ugliness all round.

The distressed wage-earner looks across the empathy bridge to be crossed and sees what Arlie Russell Hochschild describes: “New York Times at the newsstand … organic produce in grocery stores ….foreign films in movie houses … small cars … bicycle lanes, color-coded recycling bins … gluten free entrees.” (Strangers in Their Own Land) They see a gentrified class whose smug expertise in products and services, proud display of meritocratic credentials, and exclusionary guardianship of their privileged offspring seem a perversion of a working-class’ American Dream and an elitist turning away from a former middle class prosperity. Refugees, immigrants not white and not speaking English are no more than an army of scabs that the elite import and exploit with low wages for low tasks.

The dividend receiving designated elite, in their turn, see ugliness in the wage-earners “prayer, fried food, plus-sized clothing” as well as in their guns, poor teeth and dependence on wages or welfare. They perceive bigotry and racism in a demos who lean decidedly more toward white privilege than multi-racialism and multiculturalism. The story of family that the gentrifiers see in the ungentrified is filled with vestiges of patriarchy, misogyny, as well as un-liberating views of marriage, divorce, LGBTQ rights and abortion. Low education, both in terms of duration and quality, fashion all manner of obstacles to the rational, civilized goals and lifestyle of the gentrifiers. There is not much respect or credence given to those who fail to succeed in a society that measure all by financial success. “Losers” and “moochers” are not therefore fellow Americans or neighbors or peers but rather the “creatively destroyed” who have not yet faced their own extinction.

At this moment, it seems that neither side feels the need to bridge the empathy wall, one side envisioning, following President Trump’s lead, a “drainage of the swamp” and the other side envisioning the certain extinction of the other in the near future. Ironically, it seems that the “swamp” is government and its institutions, precisely what an unregulated market rule wants to drain. What seems certain is that a President Trump will not drain his own pockets nor any enabling institutions. Whether his empathy bridge with the demos will quickly break down is difficult to predict in any rational way. President Hillary Clinton’s success in bridging the empathy gap depends on filling drained pockets. Historical memory reveals that there was no need of bridge building when both economic mobility for all classes and a sound middle class existed.

2 Comments

Candice Wilmore

thanks Joe.

Candice Wilmore

thanks Joe.