From JFK to Now

Published on http://bad.eserver.org/

The question of what remains of JFK’s legacy now, fifty years after his death, or, the question of whether we are as divided now as to what JFK’s brief reign means, as back then but in different ways, are just questions which lead us to recognizing how radically altered we have become in our “habits of mind and time.”

Joseph Natoli

A restlessness has seized hold of many of us, a sense that we should be doing something else, no matter what we are doing, or doing at least two things at once, or going to check some other medium. It’s an anxiety about keeping up, about not being left out or getting behind…The older people I know are less affected because they don’t partake so much of new media, or because their habits of mind and time are entrenched. The really young swim like fish though the new media and hardly seem to know that life was ever different. But those of us in the middle feel a sense of loss. I think it is for a quality of time we no longer have, and that is hard to name and harder to imagine reclaiming.

—Rebecca Solnit, “Diary,” London Review of Books, 29 August 2013

The question of what remains of the John F. Kennedy legacy now fifty years after his death, or, the question of whether we are as divided now as to what JFK’s brief reign means, as we were back then but in different ways, are just questions which lead us to recognizing how radically altered we have become in our “habits of mind and time.”

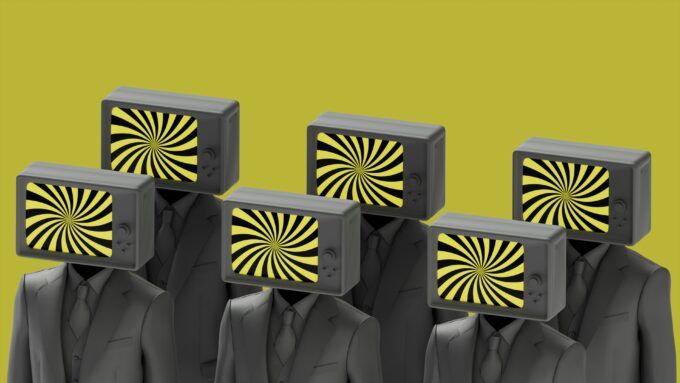

Only la commedia results from running JFK’s Camelot court through the instantaneous hashtag tweet declamations, viral YouTubes, the slash and burn “outings” of blogs, chat rooms, smash mouth radio, and Facebook photos. I don’t know what JFK would materialize at the time if he was then run through our Millennial media as steadily as we now do the Kardashians, Angela and Brad, Hilary and Obamacare. Even Bill and Monica narrowly, time wise, escaped the Millennial full Smarptphone and Twitter treatment.

Putting JFK through that full cellular and cybertreatment now, fifty years later, amounts to no more than just another viral You Tube link in our post-historical era. Except, of course, for those whose youth melded with the very beginnings of the countercultural ’60’s and mark JFK’s New Frontier as what Dylan called a “new morning,” one not only felt in politics and popular culture but in faith, as Pope John XXIII took Catholicism into its own “new morning.” We are fifty years from JFK’s assassination and now live in a restlessness that scrolls past the event or clicks to a new screen or follows a new hashtag. Those who recall what JFK meant to them thus feel Solnit’s sense of loss “for a quality of time we no longer have.” In many ways, as Wordsworth reminds us in The Prelude, “Bliss it was in that dawn to be alive/But to be young was very heaven.” Although Wordsworth refers to his early enthusiasm for the French Revolution, that level of enthusiasm continues to be felt by those who experienced the revolutionary cultural chance, of which JFK’s Camelot court was very much a part.

But consider if, back then, the JFK and Marilyn Monroe or JFK and Mafia tied Judith Campbell or JFK and a secret Swedish mistress events had been treated to the Full Millennial Media Monte. I suggest that sort of coverage would have burnt Camelot down, if and only if “habits of mind and time” remained locked in the timescape 1960-1963. This could have happened if some amalgam of H.G. Wells’ time machine and a unique Google algorithm of the American mass mindset of 1960-1963 got downloaded with the present Millennial mass mindset. JFK’s face would not be on a colorful velvet wall piece alongside Pope John XXIII: JFK’s face would have faced a media assassination before the Dallas one.

Because we all share a Millennial restlessness now, an anxiety about keeping up, about not being left behind, we all fall into a mutual way of responding, regardless of whether we feel a pang of regret for a lost way or have no awareness of any other way of responding. Now, JFK’s face, like all faces, vanishes as we turn “to check some other medium.” What the past is has become no more than a scroll far down on Facebook or a review of past tweets or a paging further than the first page of Google. Had JFK been subjected to the new democratization of reportage and representation, of response and expression, whether text or tweet, it would have been hard to name, imagine and reclaim him in his own time as attentiveness becomes too rushed to interpret and incorporate but moves on in a restless rush to this moment’s tweet. This failure or incapacity for anything to endure or impress also means that a Millennial JFK, regardless of viral videos, could have been a Comeback Kid like Bill Clinton. He could have re-entered the stage as a brand new presence, all his past scandals obliterated.

I say he could have done this based on evidence at hand that any historical/cultural memory has now given way to a digitized awareness, an awareness of hi-tech hi-speed duration. While computer memory expands with every new generation of computer, it expands to accommodate an increasing breadth of information that can be retrieved more and more quickly. Continuity and connection are not a goal here but rather global reach and access of all that is going on. Accompanying this, we now are urged to interact, redact, respond and thus shape words and events to accommodate our opinions, or, to be overwritten by those opinions. Given this situation—an opened Pandora’s Box of instantaneously accessible “information” and our unhindered license to pursue our own “likes” here—we can expect that it would be difficult to hold on to yesterday’s Facebook post or to resist the magnetism of this moment’s tweet.

There is very little in our Millennial full cyber and cell treatment to allow us to develop a continuous narrative of what is significant or insignificant. Call it historical awareness, or just history, or just memory. We are experiencing a mass cultural phenomenon resembling Alzheimer’s disease, and its relationship to the medical condition deserves exploration. This sad state of affairs is because we have forsaken interpretation for 140-character mindless tweets, as meaningless yet as potent as the shorthand calibrations of the Dow Jones. Interpretation of what anything means, whether words, images or events, is a very slow and arduous process that is not improved by having more and more stuff to be interpreted thrown at you at an ever accelerating rate. The recognition and development of continuity depends upon finding threads of connectivity, finding, in short, among all the flotsam and jetsam, among the superfluous and ephemeral, the accidental and adventitious, what matters in line with what has mattered historically.

This historical thread in no way ties the present without reprieve to what has been done before. Revolution is the result of a very forceful understanding that what has mattered historically should no longer continue to matter or to happen. An attention span that escapes the present moment not because it rejects an imposed continuity but simply because in the absence of any sense of continuity it roams randomly, cannot, ironically, bring about any revolt from a status quo, regardless of how damaging that status quo may be to planet and all its species. It also cannot hold a present event or idea or person to past realities.

You could say that nothing past sticks because no one any longer scrolls down far enough to find it. This is not a matter of personal choice, a matter of inviolable personal “freedom of choice,” but simply a result of living within very powerful priorities. Our Market Rule finds a potentially threatening critique in the past, while the present offers new markets and new profits. You could also say that in a seriously wealth divided society such as the US is in our new Millennium, those who are on the “right” side of that divide emphasize “choices,” the more the merrier, rather than a focused critique emerging from a clear recollection of the past.

The future will reveal whether we’ll have to step away to some extent from all our new devices of chatter dispersal in order to regain the steady focus that meaning and understanding require, both essential, as I say, to the construction of a continuous historical narrative. The future may also reveal habits of time and mind that overcome the restlessness and anxiety that more and faster cybertech create. Let’s hope so. The repeat of all the Vietnam stupidities in the Iraq war, as well as the repeat of the 1994 Conservative Contract with America in the 2010 Tea Party victories, as well as the repeated financial crises resulting from continued Wall Street criminality, reveal that thus far we forget more of the past as we get more Apps on our Smartphones. Tweets proliferate and Smartphones become smarter and AI beats the human brain on Double Jeopardy and GPS takes us to the spot and Apps recognize voices and so on and on. And yet our politics are dumber than any time in history; our educational system suffers in the same way education suffered in the Middle Ages; and our economy has replaced democracy with plutocracy.

So—and I shall use the “so” here consequentially, and not in line with present fad which is use “so” to dismiss whatever has been said by anyone previously and thus announce one’s one opinion—JFK, subjected to our Millennial cell and cyber coverage, would have gone viral for fifteen seconds, could have come back as if none of that ever happened, and would now, fifty years after his death, be remembered in line with the demographic that Rebecca Solnit provided in the opening quotation. The young, swimming like fish through the new media, would think JFK “old school”, his importance restricted to “back in the day”, which would be his death blow, another assassination of JFK.

Those who were young back then would return to the two questions I raised in the first sentence. They would wish I had addressed them, although I’m sure others in this Bad Subjects special issue have. Those in the middle feeling a sense of loss would be yearning for a “large, focused block” of historical memory in which to place JFK, but regret at the same time that they swim in the waters of “fragments and shards” of the past.

The regret here is dark and deep. Nothing from the past, even the bright memories of JFK’s Camelot, connects clearly, or can remain uninterrupted by an unstoppable random barrage of what a Full Monte hyper-tech throws at us in 2013.