Hunger Games Catches Fire

Published on http://sensesofcinema

“The risk of a drift toward oligarchy is real and gives little reason for optimism.”

Thomas Piketty (1)“So what do you think, now that the whole world wants to sleep with you?”

Hunger Games: Catching Fire

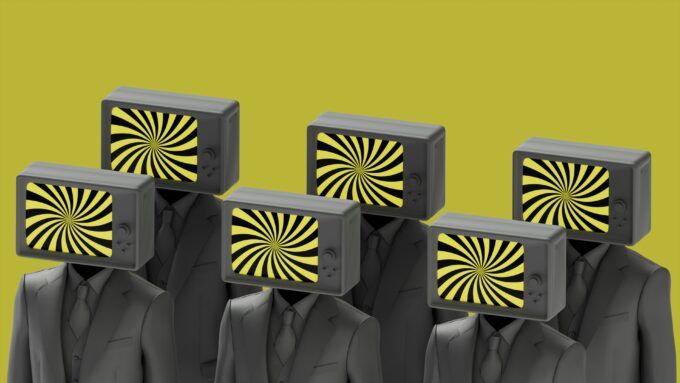

According to Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Market Rule in a number of countries, including the U.S., has set up a relentless disparity in wealth in which the owners of capital will expand their wealth while wages stagnate. The case made here is solid but not seductive. It implies that release could be organized democratically but such is forestalled by an entrapment within fantasies and illusions. These are not confined to the U.S. but most clearly displayed in this longest running middle class democracy where the top 1% hold 40% of the nation’s wealth while the bottom 80% claim only 7%.. Nowhere else is the New Gilded age gilded so clearly as in the U.S. Thus far, expanding hi-tech distractions and seductions appear to be successfully diverting a collapsed egalitarian democracy from launching any widespread revolt, from, in short, catching fire.

The Hunger Games: Catching Fire (2013) is an American film, based on novels written by an American, Suzanne Collins, which depicts a future that is an amalgam of George Orwell’s 1984 and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. The film seems to be a dramatization of a world that Piketty’s economics describes as awaiting capitalist societies that have transformed themselves into entrenched oligarchies that own the democratic processes for change. The bottom 99% in Panem are living in conditions vaguely similar to Neill Blomkamp’s 2009 film District 9 in which extraterrestrials are confined in a Gitmo-type imprisonment. The harsh working conditions are reminiscent of John Sayles’ Matewan (1987) in which a mining company with the controlling despotic power of Putin’s KGB keeps miners working hard and living poorly. You expect a reaction, a counterforce to catch fire, a John L. Lewis and the United Mine Workers to rise up. The mine workers in Hunger Games are not exposed to the brainwashing of Orwell’s 1984 nor are they taking their daily soma tablets as in Huxley’s Brave New World to keep them mellowed and very far from catching revolutionary fire. The oppressed in this film recognize their own oppression as well as their oppressors.

Meanwhile, back at Off-Screen Reality, we may be transitioning to a future in which the exploited and victimized, the cast offs of Market Rule, live in a feudalist condition and recognize this. But while such a feudal/oligarchic order is already visible, in former middle class democracies such as the U.S., there is scant recognition of how dire the situation is. U.S. Americans continue to breathe the vapours of former middle class contentment, continue the illusion that the feudal order is on the screen and not their own. The Hunger Games world is one in which 99% clearly immiserated, do not live in a bygone middle class glory, and most conspicuously different from the film’s audience, this Panem populace is not “empowered” and entranced by hi-tech but somehow excluded from its beneficences. All they have in the form of distraction are the Hunger Games, a circus in which their own kind fight to the death. This is not “us” we think. And yet there is identification between audience and screen. Subliminally or close to the surface, we feel the need to catch fire, the need not to be a Hunger Games audience, entertained by our destruction, rather like the way the male praying mantis orgasms as his mate devours him.

The Hunger Games: Catching Fire kindles a revolutionary fire on the screen that Americans cannot consciously identify with but at the same time, the viewing remains cathartic. Indeed, the dire conditions of a Have More Each Day and a Have Less Each Day divided society as well as the uses of bread & circus distractions to keep such a volcanic state of affairs from erupting are conditions both film and American society share. As each installment of The Hunger Games moves us close to on-screen revolution that drama acts as a surrogate for real revolution, in effect cools, and defuses the revolutionary energies rising in the real world. The Hunger Games: Catching Fire becomes itself a bread & circus distraction that preempts revolution.

Democracies collapsing into oligarchies seem to be the future, if not already the present, a future that seems far more probable than an Underclass, Working Class and Middle Class revolutionary alliance. Audiences now would even have to ask “Against whom are we revolting?” because all three mechanisms of release – seduction, distraction and repression – seem to be at work in fashioning an admiring and envious view of the Elite, the Winners, whom the Many, regardless of how oppressed, are all always, in this seductive scenario, only a few steps from joining.

Hunger Games both touches a very hot spot in any oligarchy – the threat of a revolt by the masses – but at the same time weakens that threat in two ways that respond particularly to U.S. culture but resonant in all Millennial hi-tech bourgeois cultures retrogressing to gentrified/peasant cultures. The American middle class illusion that their social mobility has not been deteriorating for more than a quarter of a century and that regardless of the diminished quality of their lives, they still are middle class persists. Politically and cinematically. Politically, if the middle class and the underclass join in recognition of how hard pressed they are economically by inherited wealth and a stochastic economics, revolution would indeed catch fire. But popular film must camouflage any identity between the wretches of the Panem Districts and a middle class audience. Popularity is not achieved by destroying the illusions of a mainstream audience.

A protective wall between a middle class audience and the wretched of the Earth is now built into middle class attitudes in the U.S. An invading gentrification joins the already on-going attack on what the 2012 Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney referred to as a parasitic 47% of the U.S. population. These extend beyond welfare and entitlement recipients to wage earners, to a burgeoning class of unemployed workers labeled for extinction by technology, outsourcing and an equally burgeoning financial sector in which money is made by having money and not with labour. The working wretched of Hunger Games, therefore, appear to an American middle class as disruptive, unionized workers threatening to strike rather than as working class heroes moving toward revolution. Once again, the threat of revolution by an immiserated class which an audience in the U.S. has reason to identify with is defused, though the sight of ruined faces, as in Walker Evans’ Let Us Now Praise Famous Men photos, and the grandiloquence of the privileged class is not without impact.

Distance between audience and film is further achieved by allowing the audience to think that the wretched of the Districts would not be wretched if they had access to cyberspace because cyberspace means personal freedom. Significantly, the oppressed of Panem do not share the hi-tech toys of the elite class, have only the hard drudgery of the inhabitants of Emile Zola’s Les Rougon-Macquart world and none of the self-empowering seductions of cybertech, Smart phones and social media. This absence alone enables a Millennial audience anywhere in the world to distance itself from any need to catch fire and overthrow a despotic rule. Where is the despotism when one is empowered to design the world as one chooses? Thusly, cybertech becomes the remedy to revolution, a parallel universe the audience already possesses.

This illusion that technology confers personal freedom is protected in the film so that recognition, a shocked recognition, is never made that random and feckless choices in cyberspace – defined as a space of freedom and democracy – does not translate into anything politically and economically liberating in the real world. A continued impoverishment in the real world is largely underwritten by this misperceptio

It is predictable that revolt will catch fire when only the elite enjoy a hi-tech life and there’s only the very Roman gladiatorial-like barbarism to keep the oppressed defused and distracted. The games have no penetrating psychological impact, no attempt at conditioning responses or spinning scenarios of deception. Nothing is internalized as a self-seducing mechanism. And the participants in these games to the death are not trained gladiators but randomly chosen district friends and neighbours. Besides the games themselves, which are more incendiary than palliative, it is all stick and no carrot that President Snow (Donald Sutherland) offers his people. And so, the film displays an ignorance of the dominating magic of our own Millennial 21st century world and that put simply is our branding, bamboozling, spinning, self-mesmerizing cleverness at keeping any of the many Les Miserables from catching fire.

The genius of our own time and place is to deflect attention, say from the oligarchic President Snow and his politics of immiseration in Panem, and turn it back onto the immiserated. It is a neat trick and it is performed with great skill in our own time but in this future world, we are back to a politics that Nero and Caligula relied on: brutal suppression and bread and circuses, something like a crude and primitive form of seduction.

There is a great deal then set up to catch fire here, a great deal that is unlike an American Millennial climate in which those without health care are spun toward opposing President Obama’s attempt to give it to them, in which a financial collapse resulting from Wall Street chicanery is blamed on government regulations, in which a preemptive attack on Iraq is a necessary consequence of fictitious weapons of mass destruction, in which a diminishing middle class focuses their attention on a totally collapsed underclass as the root cause of their problems. And so on. In short, the U.S. in this Millennial clime is very far from catching fire because no one is looking for matches but rather at their Smartphone or shopping online or surfing porn or sports or gambling online. And so on. And those who are ready to catch fire are themselves overheated with hatreds and animosities, fantasies and illusions that endanger themselves, others and any possibility of democratically voting sane and rational remedies. This state of affairs, once again, is not limited to the U.S. but as the excesses and extravagances of a viciously competitive society exceed all rivals, it remains the closest Panem-of-the-future.

It seems then that Hunger Games has no insight to offer as to how drastically the audience of the film are detoured from recognizing who and what is immiserating them. Rather than leading to any recognition on the part of its audience of similarities, what the film does is make very clear that there are no similarities. These District citizens have reasons to catch revolutionary fire that the audience does not have. President Obama, for many, would be a President Snow except for the fact that a challenging number are “on to him” and oppose him in every way. But more significantly than Congressional opposition is every American’s own personal opposition. Each American feels self-empowered to render any politician’s tyranny ineffectual. There’s no such self-deception revealed in the film.

The audience is led to believe that those living in Panem do not know how to empower themselves; they do not know how to be “whatever” about oligarchic rule. They are not us. The audience is made to feel that if they were living in such a clearly divided world of Tyranny and Oppressed, they would catch fire and revolt. But what is seen on the screen is not true to what the audience feels about themselves; the Panem poor are being led to revolution in the same way every Hollywood hero who has been brought low by villainy returns to vanquish villains. What movies do is to enact what we do not have to do ourselves. It is a tight formula of threat, violence, and heroic victory. If it is up there on the screen, it is as if it has been done by us. We have experienced it. We do not have to catch fire in the real world. And besides this, we were never them or in those circumstances. We do not really need the catharsis; we cannot be revolutionaries vicariously because we have no need to be revolutionary. But still, vicarious catharsis is available for those who need it.

Hollywood has proven persistently and perennially that a classic realist formula can touch upon the hottest of societal hotspots, as for instance racism in the Oscar winning film 12 Years a Slave (2013), where the audience in the U.S. is protected from any examination of their own lurking racism by the fact that the cruelties of slavery were abolished in the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation and totally resolved with MLK’s civil rights movement of the `60s. It is as if the American population had been inoculated against racism, although the bitter and irrational responses to Mr. Obama’s tenure thus far reveal that for many that inoculation failed. Racism and sexism are portrayed in the 1985 film The Color Purple but Stephen Spielberg managed to re-direct the darkness of these themes into a colourful cinematography that rivals Disney’s 1946 Song of the South. An economics of immiseration and impoverishment are sidestepped in the screwball comedies of the `30s that make the well-to-do seem lunatic and playful or forbearing and beset by the many problems wealth creates. Hard times and those who live them are inextricably linked to crime in the James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart and Edward G. Robinson films, where either redemption or a barrage of bullets ends both the criminal and any further thoughts about poverty.

However, the Hollywood formula that brings all to happy closure is about as airtight as a sentence in Jacques Derrida’s view. Both real feeling and real thought remain in the last scene of the 1950 John Garfield movie The Breaking Point as the camera pans back on a young black boy, a solitary figure, wondering what has happened to his father who has been murdered and will never return. I see that boy’s concern as invisible in that mid-century moment, the boy who will in two years appear as a man in Ralph Ellison’s novel, Invisible Man. Poverty too has not been totally defused by the Hollywood classic realist formula producing escapist, bourgeois melodrama. Abraham Polonsky’s Force of Evil (1948), Robert Rossen’s Body and Soul (1947), and John Berry’s He Ran All the Way (1951) – all overflow containment. The hunt for Communist subversives and their work ended much of the direct depiction of awful wealth and awful poverty in the U.S. Italian neo-realism represented in films such as Roberto Rossellini’s Città aperta (Rome Open City, 1945), Luchino Visconti’s La terra trema (1947); Vittorio de Sica’s Sciuscia (Shoeshine, 1946), Ladri di biciclette (Bicycle Thieves, 1948), and Umberto D (1952) succumbed to both the influx of American escapist film as well as Italy’s own rejection of the “dirty laundry” image of Italy projected in such films.

While Italian film neo-realism responded to the literary verismo of late 19th century Italian authors, such as Giovanni Verga, itself based on a French naturalism of Zola and Guy de Maupassant, the Hunger Games films are based on mass-market bestsellers, a trilogy which has about 26 million copies in print. Although the lives of district workers are as downtrodden, their misery is a faintly sketched backdrop to Katniss Everdeen (Jennifer Lawrence) herself, a bold Diana, a huntress, who goes through all the costume changes of a Burlesque star. Comparable to the threat of revolution, Katniss threatens to deconstruct an image of a dominating male and a submissive female, a deconstruction already underway and not restricted to the U.S. It is at this point, that the promise of a classic realist formula to settle all that has been unsettled is tested.

Apollo, Katniss-Diana’s twin, is here Peeta Mellark (Josh Hutcherson), one who would have been a casualty in more than one instance if not for Katniss’s protection. She looks after him as if they were bonded as twins. His vulnerability and her heroic valour reverse the normal expectations of the classic realist formula. The male here is the weaker of the two, which positions every male in the audience, in short, against the grain of their own vicarious identification. On whose coattails will they ride into the film? This audience/screen identification is essential if the film is to have any impact, if the film is to be brought into one’s own life without destroying one’s defenses, illusions and presumptions. The hot spot of revolution has been re-routed to audience entertainment but can the same cinematic legerdemain do the same with the hot spot issue of male dominance?

Katniss, in the role not only of formidable huntress but also transforming slowly in film after film, to Libertas, the Roman goddess of freedom, the French goddess of Freedom and Democracy, is at once also Persephone, the innocent ingénue of romance before her seduction, and a Circe, a seductive temptress. She is therefore multiply valenced to displace her assumption of the masculine. Finnick Odair (Sam Claflin) and Gale Hawthorne (Liam Hemsworth) assert a masculine presence that counters Peeta’s weakness and at the same time bring Katniss into a conventional boy/girl relationship that allows the male audience to recognize her as not a threat to their own masculinity but as an object of their desire and passion. Her toughness is no longer intimidating. She is hot and so the hot spot of a threatened male dominance is cooled.

In this intermingling of sexuality and dominance, one the archetypal possession of the female, the other of the male, the film attaches itself to what an entire 21st century global culture is invested. 57% of professional and technical workers in the U.S. are women. Women are either the sole or the primary earner for her family in four in 10 American households, four times the number in 1960. Women control 65 percent of global spending and more than 80 percent of U.S. spending. According to Fast Company’s Co Design, (www.factcodesign. com), globally, women consumers control $20 trillion in consumer spending. They make the final decision for buying 91 percent of home purchases, 65 percent of the new cars, 80 percent of health care choices, and 66 percent of computers. In the U.S., women rule the blogosphere. These are facts marketers have to respond to but they also mean that the classic realist formula for drawing an audience into a drama of identification, threat, and resolution, or, happy closure, or at least, a soft landing, is going to reflect the cracking of the egg and a new setting of the omelet. A woman will win the games and she will light the fire of revolution but at the same time, she will be that familiar object of male desire. She will succumb to the male gaze, which means she will somehow keep Peeta alive, mobilize a revolution and at the same time be the ingénue who must be kept alive, be at the same time the hero who launches the revolutions and the lady in distress saved by the revolution.

There is nothing new in women pushing men off the hero pedestal in film but new moves on the cultural chessboard, mostly economic, make Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974), Thelma & Louise (1991), Norma Rae (1979) liberation neither pertinent nor helpful. The real precedent for Jennifer Lawrence’s portrayal of Katniss comes from her own portrayal of Ree Dolly in the 2010 film Winter’s Bone. Facing the same poverty of her fellows in Hunger Games, Ree acts boldly to save the family homestead. But this independent film does not attempt to lean heavily into a sexual seductiveness; Ree can remain a resilient figure out of Grapes of Wrath. The Hunger Games’ popular box office aims require a female lead who somehow miraculously is a romantic ingénue and a lethal huntress of all, including the male.

The greater danger to an audience being entertained and not upset in this film then is not oligarchic power, the feudal conditions that result and the threat of violent revolution, but Katniss herself, a woman more adapted to surviving than any man. Societies moving away from male oriented jobs in construction, manufacturing, agriculture, fishing, mining, lumbering and toward information age hi-tech jobs value relationship skills, flexibility, patience, compromise and dialogue which women exhibit more prominently than men. Americans after the Great Recession are keenly aware that men were hit harder during the recession with both a higher level of unemployment and a larger percentage increase in the rate of unemployment. They are also aware of the looming extinction of jobs that working class men formerly filled. Rising female power is not restricted to the U.S. Fraser Nelson in The Spectator writes: “For anyone born after Perry Como was in the charts, women are no longer underperforming. When law and medicine graduates are 60pc female, and girls a third more likely to apply to university than boys, we’re not looking at equality. We’re looking at a new inequality being incubated, because male horizons are narrowing.”

Katniss’s dominance, her unwavering boldness and strategic smartness on the competitive field resonates with the leadership skills of a corporate CEO who maneuvers his company with lethal but legal force in the global competitive arena. But Katniss’s CEO qualities are not those displayed by Meryl Streep in The Devil Wears Prada (2006), or Demi Moore’s Meredith Johnson in the 1994 film Disclosure. For Hollywood, a woman who has corporate power is a “power bitch.” This transfer of Katniss to the corporate boardroom, a transfer already underway in many societies, has not the abrasiveness or challenging aspects of Linda Fiorentino in The Last Seduction (1994) or the “more deadly than the male” role Charlize Theron plays in the 2003 film Monster. And these are still distant from Ann Savage as Vera in the 1945 film Detour. The woman who threatens male dominance must always be cast as a femme fatale or mentally deranged. Neither is Katniss Ursula Andress’s “she who must be obeyed” in 1965 film She or like the computer female, Samantha (Scarlett Johansson), in Spike Jonze’s Her (2013), a woman imagined to be what Joachim Phoenix’s Theodore wants her to be. Scarlett Johansson’s predatory and beautiful alien in Under the Skin (2013) is both a threat to men and a woman objectified within the male gaze. The combination is fatal to men, which is not the case with Katniss’s blending of threat and attraction.

A strong woman, sexually attractive and romantic at heart at the same time can fulfill all the attributes of heroism typically assigned to men. But this revelation, like the real threat of revolution, is buffered in the clever fashion popular film always buffers its audience from any disconcerting contact with what is real but too often not entertaining, and therefore seldom profitable.

Endnotes

1. Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, translated by Arthur Goldhammer, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2014.

2. Fraser Nelson The Spectator (July 12, 2013).

2 Comments

Jon Hendy

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N0p1t-dC7Ko&sns=em

Jon Hendy

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ceegnWSENQ&sns=em